In our new series of articles, we delve deeper into the microcomputer revolution. We explore the emergence of the first microcomputers in Slovenia and the development of domestic microcomputer production. The series covers various stages and aspects of microcomputing, its impact on the development of personal computing, general connectivity, and computing culture within society.

The concept of DIY (do-it-yourself) has been integral to microcomputing since its very beginnings. Driven by the desire for affordable construction and personal use, it played a significant role in the emergence of classic home computers. This approach also greatly strengthened computing culture in society. DIY enthusiasts often formed microcomputer clubs, which popularized microcomputing and facilitated the exchange of ideas, knowledge, hardware, and software. They created a new retail market for microchips and other components, sparking the growth of specialized computer devices. In Slovenia, microcomputer clubs began forming in the early 1980s, bringing with them a DIY and hobbyist microcomputing subculture, along with all the associated trends.

Microcomputer Culture and DIY

With the rising standard of living in developed countries, hobby electronics also saw significant growth. Areas like amateur radio and model building became well established. Naturally, amateur microcomputing gained popularity among these electronics enthusiasts. By around 1974, thanks to microprocessor technology, they could start building their own devices. Hobbyists approached microcomputing with characteristic enthusiasm and pride, which quickly became infectious, especially among young people. Most devices were assembled from DIY kits, though many enthusiasts also ventured into building them independently.

Even the first-generation microcomputers were typically available in two forms: as fully assembled devices and as DIY kits. A good example includes microcomputers like the MITS Altair 8800, Altair 680, and IMSAI 8080. They were purchased by both professional and hobbyist users with basic skills for constructing electronic devices. The kits usually included a bare printed circuit board, microchips, and various other components. Buyers would manually install and connect all the electronic parts themselves. The completed devices were often housed in enclosures made of wood or other inexpensive materials. DIY microcomputers generally had limited capabilities, a trend that eventually led to the popularity of the simple single-board computer.

Single-board microcomputers

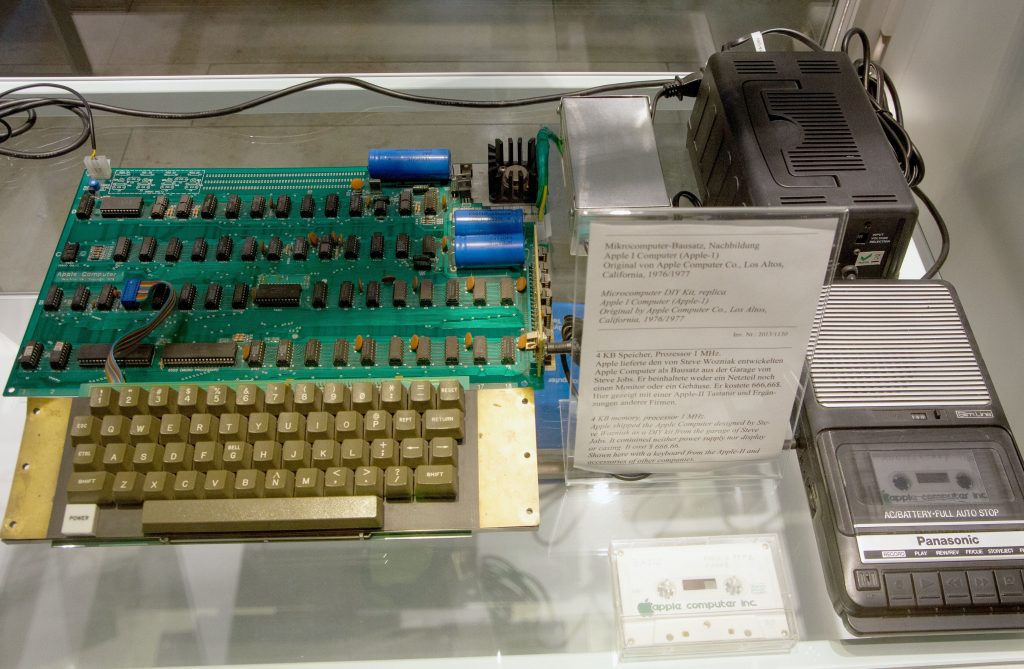

The design of the single-board microcomputer was significantly simplified and made more affordable by Ohio Scientific with the Superboard. This microcomputer was built using a minimal number of microchips, some of which were custom-made for this purpose. The microcomputer components were integrated into a complete unit that included a power supply and a keyboard. Around the same time, Steve Wozniak designed the Apple I as a DIY microcomputer, and it was the first to include a graphics controller. This marked a gradual evolution of the development board concept and represented an important step toward affordable home computers. A typical development board featured only a microprocessor, very limited working memory, and the essential support circuitry.

With devices like the Superboard II and Apple I, designers began placing greater emphasis on user interfaces. They incorporated a graphics controller, a keyboard interface, and a cassette tape controller, while also expanding the memory. The relatively high interest in such devices fueled further development, steering the market increasingly toward pre-assembled, ready-to-use machines. The basic Superboard II kit was available for purchase at around $300. It was also introduced in the UK under the name Compukit UK 101. By 1980, manufacturers released even more refined versions of single-board DIY microcomputers. Instead of the inexpensive MOS 6502 processors typical of the Superboard and Apple computers, these newer models often featured variants of the Zilog Z80.

The Explosion of Personal Microcomputing

In England, Sinclair introduced the ZX80, the first microcomputer priced under 100 pounds (around 40 dollars), followed by Acorn’s Atom. In 1981, the even more successful Sinclair ZX81 was released, available in kit form for just 50 pounds. Despite its limited capabilities, the computer became a massive hit, with one and a half million units produced, sparking a boom in software development. Alongside these devices focused on cost reduction, simplification, and downsizing of microcomputer mainboards, larger single-board systems also emerged. Among these, the most influential was the Ferguson Big Board, which integrated the full capabilities of more expensive business microcomputers running the CP/M operating system onto a single board.

The Sinclair ZX81 is one of the last such microcomputers available in kit form and marks the beginning of the era of fully assembled home microcomputers, more accessible for ordinary private users. It was also the first widely available microcomputer in Slovenia. In 1982, the first limited batches arrived on the domestic market. The price was higher than abroad, but still lower than the average monthly salary in Slovenia. Within a year, there were already around 200 users in Ljubljana. Inspired by the ZX81, enthusiasts in the Ljubljana Microcomputer Club also created their own DIY microcomputer, the Abakus.

DIY microcomputer Abakus

The first microcomputer club in Slovenia was founded in 1980 by the Union of Popular Technology in Ljubljana. Its purpose was to bring together users and enthusiasts, as well as promote microcomputer culture. The club aimed to provide local enthusiasts with access to affordable microcomputer technology, so they immediately began designing a simple DIY single-board microcomputer. They divided responsibilities for different parts of the computer. Initially, they created a wired prototype, and after testing, they ordered the first ten printed circuit boards from a local craftsman. The Abakus computer was finalized in spring 1982, and it was first publicly presented at the Electronics Fair. At that time, the club had 80 members.

The DIY microcomputer Abakus, in its minimal configuration, featured a Zilog Z80 microprocessor and a working memory (RAM) ranging from 2 to 6 KB on a single board. It included capabilities for connecting a television and an additional cassette player for running programs and storing data. A bus and an interpreter for the BASIC programming language were also available. As a society, they were not allowed to engage in serial production. However, they prepared detailed technical plans for both hardware and software and offered the microcomputer for serial production to several domestic manufacturers. There was some interest from Iskra, but they ultimately used a more modern design for their HR84 microcomputer, inspired by the popular Tandy TRS-80 Color.

Users could assemble the computer without a case or additional equipment for just $200, while adding extra components would bring the total to around $500. More powerful and equipped business microcomputers like Partner and personal computers such as Dialog were priced at approximately $8,000 (equivalent to 100 average salaries in Yugoslavia). Superior foreign microcomputers, such as the Apple II, cost even more than $10,000, at least four times the price abroad.

Build-It-Yourself computers in Yugoslavia

Self-building for private users in Yugoslavia became especially important due to strict import restrictions, which prevented individuals from importing goods worth more than 50 German marks (20 dollars). After 1984, emigrants could bring in some more equipment, but still not even the cheapest home computers. The Slovenian government proposed the complete removal of restrictions on home computers, but it was not accepted by the federal government. This led to a significant rise in the smuggling of hardware, as well as, similarly to Eastern Bloc countries, the piracy of software. For a long time, there were no suitable domestic home computers, and when they finally appeared, they were not competitive with the smuggled devices.

Due to the acute shortage of computers, many private users turned to domestic self-building projects. The plans for self-builds were first published in the Informatica journal by experts from the Department of Computer Science and Informatics at the Jožef Stefan Institute in 1978. However, the journal’s reach was limited to professional users. Initially, they published a plan for a self-built Vita microcomputer, using the Motorola 6800 processor. This microcomputer was compatible with the Iskradata 1680 but was built on a single board. This was followed by articles on additional interfaces, and in 1984, a plan for a self-built computer named Petra, compatible with the IBM PC. Self-building truly gained momentum in our country only with the self-built microcomputer Galaksija.

Microcomputers Galeb and Orao

Inspired by the homebuilt Superboard 2 and UK 101, in 1981 Miroslav Kocijan began developing a microcomputer in Croatia. He took the original design of the Superboard 2, which featured the MOS 6502 microprocessor and 8 KB of RAM, and added an expansion bus and an RS-232 serial connection. The computer, named Galeb, was not intended to be sold as a homebuilding kit but rather as a ready-assembled device, for which Kocijan made an agreement with the company PEL in Varaždin to produce a larger batch. However, the Galeb computer did not reach serial production until 1984, by which time its design had already become outdated. Only about 250 units were made and sold.

The upgrade, named Orao, was introduced later that same year. It was designed with fewer components to facilitate mass production and reduce the final price. The RAM was increased to 32 KB, and the 16 KB ROM included not only the BASIC interpreter but also a simple boot program. The graphics and sound capabilities were improved. The new graphics controller allowed for the display of black-and-white images with eight shades and a resolution of 16×16 characters, while the sound controller could generate sounds through the built-in speaker across a range of five octaves. The Orao microcomputer was initially intended to be sold for under 500 dollars, but the price eventually rose to 600 dollars.

The company was overwhelmed with around 3,000 orders after the first trial batch. In the following years, the Orao became the most widespread microcomputer in Croatian schools. A few were also purchased for equipping Slovenian schools. Its popularity was partly due to its partial software compatibility with the Apple II microcomputers, which dominated the educational sector and had become particularly successful in Croatia during that time. The company Velebit was responsible for the import of Apple II computers, the distribution of compatible microcomputers from the company Ivel, and the Orao microcomputers.

The homebuilt microcomputer Galaksija

The most well-known and successful Yugoslav homebuilt microcomputer was introduced in 1983 in a special edition of the magazine Galaksija titled Računari u vašoj kući. The author, Voja Antonić, aimed to offer users in the underdeveloped domestic market a simple and affordable option for homebuilding. Enthusiasts could obtain all the components through the Galaksija magazine. They arranged for the import of microchips from Austria and the distribution of components. Mechanical keyboards were produced at the Institute for Electronics and Vacuum Technology in Ljubljana, while printed circuit boards and templates were made by the companies MIPRO and Elektronika Buje. They also published a manual for using and programming the computer and regularly published programs.

The Galaksija was designed after other inexpensive homebuilt microcomputers on a single board. It consisted of a Zilog Z80A microprocessor running at a reduced clock speed of 3 MHz and eighteen supporting microchips. Users could install between 2 to 6 KB of RAM, which could be expanded via the expansion bus to a maximum size of 54 KB. The processor’s clock speed was reduced because, like the Sinclair ZX81 computers, it also handled the display of 32×16 characters on the screen. The instructions for displaying characters were stored in a 2 KB ROM. It allowed connection to a black-and-white monitor or a regular television. The data transfer and writing speed to the cassette tape was very limited.

The author, Voja Antonić, personally equipped the read-only memory (ROM) chips. On the main ROM (ROM A), he installed the boot program and the interpreter for the Galaksija BASIC programming language. On an additional ROM (ROM B), he installed an extension for the interpreter, the assembler, and the debugger. In several companies, the computers were also assembled for users and placed into cases. Thanks to its low price, adaptability, and availability, the Galaksija became the most widespread home microcomputer in a few months, achieving cult status. In total, around 8,000 units were produced, both as homebuilt and pre-assembled versions.

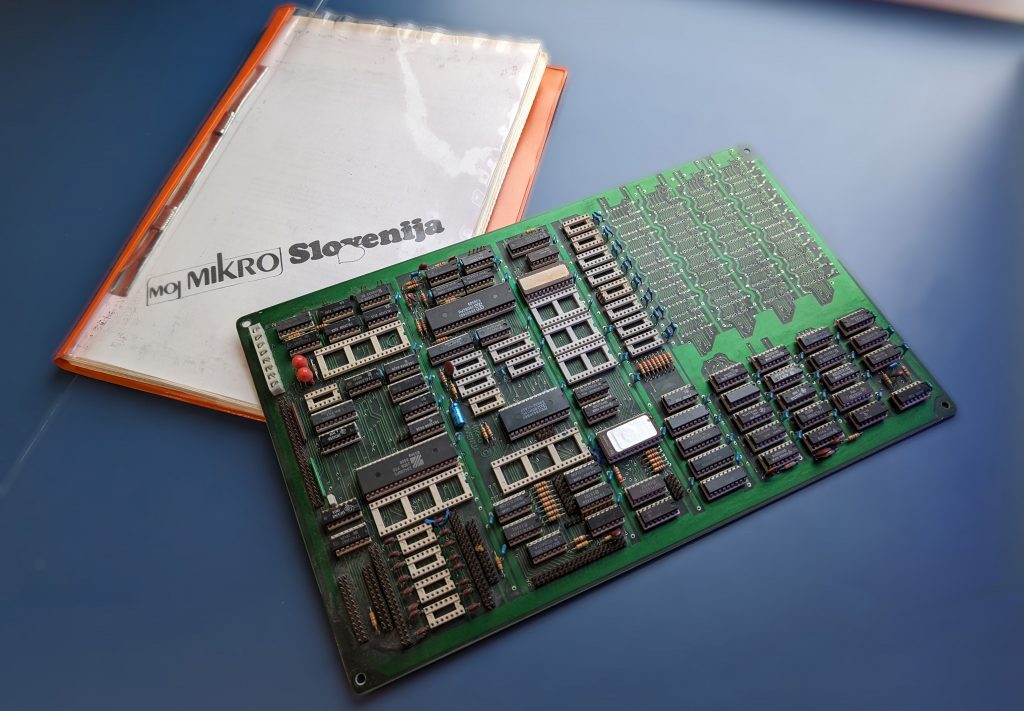

The homebuilt microcomputer Moj Mikro Slovenia

In 1985, the computer magazine Moj Mikro offered a series of homebuilt kits for local enthusiasts, inspired by the Ferguson Big Board. They arranged for the import of microchips and other components from Italy and distributed them. Detailed instructions for homebuilding and programming the microcomputer were provided, along with equipped read-only memory (ROM) chips. For some time, the magazine regularly published details about hardware and software, as well as answers to users’ questions. They also published hardware extensions to expand the working memory up to 256 KB and enable the use of the Intel 8088 microprocessor with the MS-DOS operating system. Some users were dissatisfied with the lack of a cassette controller.

The board contained one of the versions of the Zilog Z80 microprocessor, 64 KB of RAM, and an additional memory bank for read-only or working memory with a size of 8 KB. It included a controller for two serial and parallel connections, a keyboard controller, and a timer. The graphics controller could display an image with 24×80 characters on a computer screen or television. The disk drive controller enabled the use of the CP/M operating system. Users could purchase the basic homebuilt kit, without the case, power supply, and disk drive, for around 350 dollars. In the winter of 1986, another batch of homebuilt kits was produced, though the exact number of units sold is unknown.

Miha Urh

References

Informatica (1978, Volume 2, Issue 1) (LINK) | Delo (15.05.1982, Volume 24, Issue 111) (LINK) | Delo (17.05.1983, Volume 25, Issue 112) (LINK) | Delo (21.12.1983, Volume 25, Issue 294) (LINK) | Delo (05.06.1984, Volume 26, Issue 129) (LINK) | Sobotna priloga (16.06.1984, Volume 26, Issue 139) (LINK) | Informatica (1984, Volume 8, Issue 4) (LINK) | Moj mikro (Julij/Avgust 1984, page 14) (LINK) | Moj mikro (September 1984, page 21) (LINK) | Delo (02.02.1985, Volume 27, Issue 27) (LINK) | Moj mikro (April 1985, page 6) (LINK) | Moj mikro (Julij 1985, page 12) (LINK) | Moj mikro (Avgust 1985, stran 24) (LINK) | Moj mikro (September 1985, page 14) (LINK) | Moj mikro (December 1985, page 16) (LINK) |

Wikipedia: Ohio Scientific | Compukit UK101 | Apple I | Ferguson Big Board | ZX80 | ZX81 | Galeb | Orao | Galaksija